Updated: February 2020

Creating a static website involves an almost infinite set of choices. Among these is

Gatsby – a static site framework based on React, JSX, CSS-in-JS and

many other modern approaches. Gatsby is, in many ways, the JavaScript successor to

Jekyll. I’ve upgraded several sites to Gatsby (including this one) finding

a way to integrate TypeScript as part of the journey.

In this post I am going to work through all of the pieces of a default Gatsby site and try to explain them along the way. Included in this post are some of the reasons why I’ve chosen one particular plugin or skipped another. Often – especially when you choose a default Gatsby starter – it is difficult to understand how all of the pieces fit together, or how you might build your own starter template. Hopefully this post provides some helpful examples.

Also: the Gatsby documentation is extremely good. There is a fantastic tutorial, quick start and some recipes. I’ve relied on those and a host of other blogs when working on this post.

In order to follow this, you’ll need access to a terminal (or console) and you’ll need Node, Node Version Manager, and git installed.

All of the code (and commits) are available on GitHub: https://github.com/example-gatsby-typescript-blog/example-gatsby-typescript-blog.github.io

Getting started

To get started, we’ll follow the quick start. First, install the Gatsby CLI (command line interface):

npm install -g gatsby-cliNext, we’ll want to create a new Gatsby site. In this post we’ll assume that our site is called (rather uninspiringly) example. Run the following command (it will generate a new folder called example where you run the command):

gatsby new exampleChange directory to newly created folder example:

cd exampleThe new command created a project folder and automatically installed our node modules and setup defaults. The project structure should look like:

example/

|

|- .git/

|- .gitignore

|- .prettierignore

|- .prettierrc

|- LICENSE

|- README.md

|- gatsby-browser.js

|- gatsby-config.js

|- gatsby-node.js

|- gatsby-ssr.js

|- node_modules/

|- package-lock.json

|- package.json

|- src/

| |- components/

| | |- header.js

| | |- image.js

| | |- layout.css

| | |- layout.js

| | |- seo.js

| |- images/

| | |- gatsby-astronaut.png

| | |- gatsby-icon.png

| |- pages/

| | |- 404.js

| | |- index.js

| | |- page-2.jsWith this, we already have enough to run Gatsby and view our site. Run:

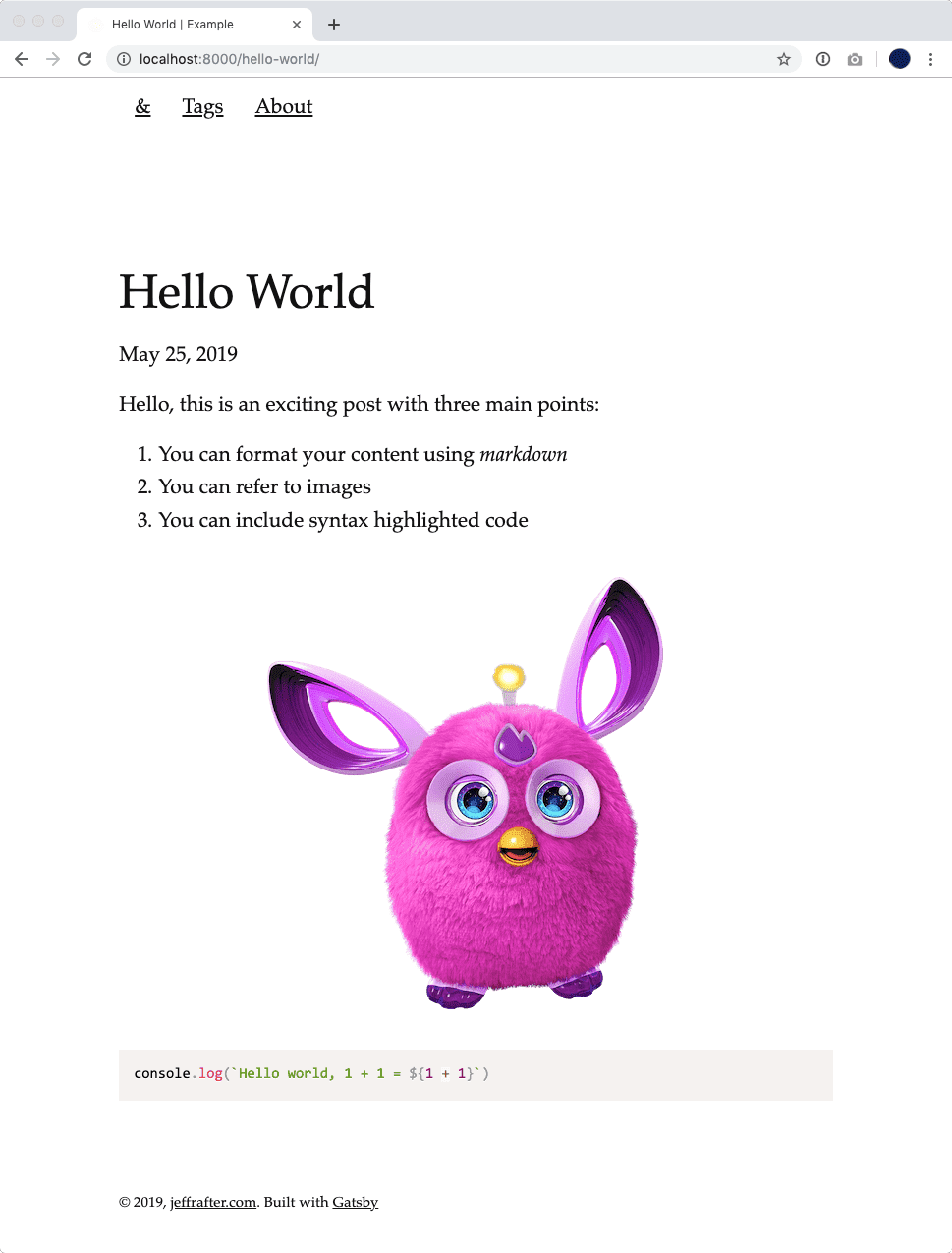

npm startThis will start Gatsby in develop mode. Open a browser to http://localhost:8000 and you should see:

The default covers the basics but isn’t very personalized. Let’s work on that now.

Configuring the node version

Gatsby requires Node to run on your computer. If you have multiple local projects on your computer, you might run into a conflict about which Node version should be used. Node Version Manager solves this problem. After installing a Node Version Manager, check which version of Node you have installed:

nvm lsIf you don’t have the version you want, find a remote version:

nvm ls-remoteThis will show lots of versions. Find the last one with LTS (for Long Term Support). Generally LTS versions are very stable. Install it using:

nvm install 12.16.1To control which version of Node should be used in our project, we’ll add a .nvmrcNotice that the .nvmrc file starts with a "." (period). By default on most systems this creates a hidden file. Oftentimes general project config is hidden away. On MacOS you can show hidden files in Finder by running defaults write com.apple.finder AppleShowAllFiles -bool true and restarting Finder. If you want to list hidden files in your console use the -a parameter: ls -a. file (within the project directory):

12.16.1The file is pretty simple; just the version. At the time you read this there may be a newer version of Node. You can also find the latest version at https://nodejs.org.

Once you’ve created the .nvmrc file, run:

nvm useYou should see:

Found '.nvmrc' with version <12.16.1>

Now using node v12.16.1 (npm v6.13.4)Ignore some things

We plan to use git to keep track of our changes. The default Gatsby starter has already initialized our project to use git. As we work on our project locally, there will be a lot of files we create but we won’t want to keep track of (because they are specific to our machine or for security reasons); we’ll want to ignore them. To do this we’ll need a .gitignore file.gitignore also starts with a "." and you can start to see a pattern emerge.. These files can be very short and specific, or they can be very long and general. Luckily, Gatsby has created this for us already. If you are looking for more examples of what might go in a .gitignore file, you can check out https://github.com/github/gitignore.

Take a look at the provided file. Notice that we are ignoring environment (.env*) files. We’ll use these later to setup values specific to our development or production environments. For more information on environments see Environment Variables.

Keeping things clean

People have different preferences when they edit code. Some prefer tabs over spaces. Some want two spaces instead of four. Some prefer semicolons and some don’t. It shouldn’t matter right? Actually it does. If editors are auto-formatting code based on user preferences, it is important to make sure everyone has chosen the same set of defaults. This makes it easy to tell what changed between versions – even when different developers (with different preferences) have made changes.

Prettier & .prettierrc

Gatsby automatically includes support for Prettier. Prettier works to auto-format your code based on a shared configuration. The default configuration is setup in the .prettierrc file:

{

"endOfLine": "lf",

"semi": false,

"singleQuote": false,

"tabWidth": 2,

"trailingComma": "es5"

}This is a fairly safe set of defaults. I tend to use the following .prettierrc configuration:

{

"endOfLine": "lf",

"semi": false,

"singleQuote": true,

"tabWidth": 2,

"trailingComma": "all",

"bracketSpacing": false,

"jsxBracketSameLine": true,

"printWidth": 120

}You might have different preferences in your project. That’s fine, so long as all of the developers working on the code agree. For more information on the available options, view the Prettier docs.

There are some files in our project that we shouldn’t (or don’t want to) prettify. The reasons we might not want to run Prettier vary but include: different formatting preferences, external libraries, generated files, frequency of change, or speed. Luckily we can tell Prettier to ignore files. The default .prettierignore file should be good:

.cache

package.json

package-lock.json

publicConfigure your editor

This section is completely optional. This is here mostly so I can copy and paste the configuration for myself. 🎡

If there are several people working on your project, the chances are high that they use different editors for their code. At the very least their settings might not be consistent. In some cases, the editors might not have support for Prettier. You can provide hints to their editors. This can be done by including a generic .editorconfig file (based on the format from https://editorconfig.org). Create .editorconfig in your project and add the following:

root = true

[*]

indent_style = space

indent_size = 2

charset = utf-8

trim_trailing_whitespace = true

insert_final_newline = trueDepending on the editor this may or may not be used. For example, you might be using Visual Studio Code. In that case you can add some additional configuration. To do that, you can create a .vscode folder with the settings for your project.

Create the folder:

mkdir .vscodeAnd in that folder make settings.json

{

"editor.tabSize": 2,

"editor.insertSpaces": true,

"editor.renderWhitespace": "boundary",

"editor.rulers": [120],

"editor.formatOnSave": true,

"files.encoding": "utf8",

"files.trimTrailingWhitespace": true,

"files.insertFinalNewline": true,

"typescript.tsdk": "node_modules/typescript/lib",

"search.exclude": {

"public/**": true,

"node_modules/**": true

}

}eslint

Note: a previous version of this post used

tslintto add TypeScript support. It is now recommended to useeslintwhich includes the functionality oftslint.

Using Prettier and configuring our editor helps keep our code clean. Even with these tools we will still want to check our code for problems. Linters do exactly that. They can be configured to check our files for syntax errors, missing types, formatting problems and more. “Linting” is very similar to using prettier and in fact eslint and prettier can work together.

To configure eslint, create a new file called .eslintrc.json:

{

"parser": "@typescript-eslint/parser",

"plugins": ["@typescript-eslint", "prettier", "react", "react-hooks"],

"extends": [

"eslint:recommended",

"plugin:@typescript-eslint/recommended",

"plugin:prettier/recommended",

"plugin:react/recommended"

],

"rules": {

"prettier/prettier": [

"error",

{

"singleQuote": true,

"trailingComma": "all",

"bracketSpacing": false,

"printWidth": 120,

"tabWidth": 2,

"semi": false

}

],

"react/prop-types": [

"error",

{

"skipUndeclared": true

}

],

"react-hooks/rules-of-hooks": "error",

"react-hooks/exhaustive-deps": "warn"

},

"settings": {

"react": {

"version": "detect"

}

},

"env": {

"browser": true,

"node": true,

"jest": true,

"es6": true

},

"parserOptions": {

"ecmaVersion": 2018,

"sourceType": "module"

}

}Notice that we’ve disabled the prop-types validation. In React, prop-types can be used to validate the properties submitted to your components. Unlike TypeScript, which is used during development, prop-type validation is used at runtime. There are some cases where this distinction can be extremely helpful, but I generally find TypeScript’s type checking sufficient for my Gatsby sites. If you would like to generate runtime prop-types when building your Gatsby site, check out gatsby-plugin-babel-plugin-typescript-to-proptypes (though you will still need to disable the eslint rule for development).

To ignore specific folders and files, create a new file called .eslintignore:

*.js

.cacheHere, we’re ignoring all JavaScript files (so that we can focus only on TypeScript).

We’ll need to install some additional support (we can run this now, but we’ll look more at the packages we’re using a little later):

npm install --save-dev \

eslint \

@typescript-eslint/eslint-plugin \

@typescript-eslint/parser \

eslint-config-prettier \

eslint-plugin-prettier \

prettierSave your progress using version control

At this point we really haven’t added anything to the default (except a lot of configuration). Even though our website isn’t even a website yet – it still makes sense to save our work. If we make a mistake having our code saved will help us. To do this we’ll use git - a version control software that lets us create commits or versions as we go.

By default Gatsby creates a git repository and the default files have been added to it. Generally, I use GitHub DesktopIt might surprise you but some of the top coders at GitHub including cheshire137 use GitHub Desktop and micro-commit; that is, they make lots of very small commits for every change they make. This makes it easier to look back at their change history and see each step along the way to solving a problem or implementing a feature.; however, I’ll use the command line here.

You can check the status of your changes and repository:

git statusYou should see:

On branch master

Changes not staged for commit:

(use "git add <file>..." to update what will be committed)

(use "git checkout -- <file>..." to discard changes in working directory)

modified: .prettierrc

Untracked files:

(use "git add <file>..." to include in what will be committed)

.editorconfig

.eslintignore

.eslintrc.json

.nvmrc

.vscode/

no changes added to commit (use "git add" and/or "git commit -a")Let’s get ready to create a commit by adding all of the files:

git add .Here the . means: “everything in the current folder”. But what are we adding it to? We are adding it to the commit stage. Let’s check the status again:

git statusYou should see:

On branch master

Changes to be committed:

(use "git reset HEAD <file>..." to unstage)

new file: .editorconfig

new file: .eslintignore

new file: .eslintrc.json

new file: .nvmrc

modified: .prettierrc

new file: .vscode/settings.jsonWe’re getting ready to add the new files (and modify one file) to our repository. Let’s commit:

git commit -m "Add more configuration"This creates a commit with the message we specified. The commit acts like a save point. If we add or delete files or change something and make a mistake, we can always revert back to this point. We’ll continue to commit as we make changes.

Packages & Dependencies

For almost any Node project you’ll find that you use a lot of packages – you’ll have far more code in your node_modules folder (where package code is stored) than your main project (for example in your src folder).In fact the size of the node_modules folder has become a meme:

By default, Gatsby has created a package.json. Within the package.json, you’ll find metadata about your project as well as a list of dependencies used by Node (and Gatsby). The metadata in package.json isn’t used by Gatsby but the list of dependencies are used.

The default package.json look like this:

{

"name": "gatsby-starter-default",

"private": true,

"description": "A simple starter to get up and developing quickly with Gatsby",

"version": "0.1.0",

"author": "Kyle Mathews <mathews.kyle@gmail.com>",

"dependencies": {

"gatsby": "^2.19.7",

"gatsby-image": "^2.2.39",

"gatsby-plugin-manifest": "^2.2.39",

"gatsby-plugin-offline": "^3.0.32",

"gatsby-plugin-react-helmet": "^3.1.21",

"gatsby-plugin-sharp": "^2.4.3",

"gatsby-source-filesystem": "^2.1.46",

"gatsby-transformer-sharp": "^2.3.13",

"prop-types": "^15.7.2",

"react": "^16.12.0",

"react-dom": "^16.12.0",

"react-helmet": "^5.2.1"

},

"devDependencies": {

"prettier": "^1.19.1"

},

"keywords": ["gatsby"],

"license": "MIT",

"scripts": {

"build": "gatsby build",

"develop": "gatsby develop",

"format": "prettier --write \"**/*.{js,jsx,json,md}\"",

"start": "npm run develop",

"serve": "gatsby serve",

"clean": "gatsby clean",

"test": "echo \"Write tests! -> https://gatsby.dev/unit-testing\" && exit 1"

},

"repository": {

"type": "git",

"url": "https://github.com/gatsbyjs/gatsby-starter-default"

},

"bugs": {

"url": "https://github.com/gatsbyjs/gatsby/issues"

}

}Let’s customize this a bit. Change the name and description fields to something relevant. Set the author field to your name and emailKyle Matthews is the creator and founder of Gatsby. Don't worry about removing him as the author. His name is there because he built the Gatsby Starter Default. For your blog, you're the author. and double-check the license, changing it as needed. If you need help picking an open source license, you can find one that fits your project (MIT is a good default).

The default dependencies in package.json are a good foundation but we’ll be adding a few more. Notice that some of the dependencies are devDependencies. These development dependencies are only needed while we’re developing our Gatsby site.

If you wanted to install the packages from the command line you could run:

Note: you shouldn’t need to do this if you have setup Gatsby using the quick start.

npm install --save \

gatsby \

gatsby-image \

gatsby-plugin-manifest \

gatsby-plugin-offline \

gatsby-plugin-react-helmet \

gatsby-plugin-sharp \

gatsby-source-filesystem \

gatsby-transformer-sharpAdditionally, because we’ll customize some parts of the site we’ll need the React packages:

Note: again, you shouldn’t need to run this if you’ve run the quick start.

npm install --save \

prop-types \

react \

react-dom \

react-helmetIn addition to the default packages we’ll want to install a few more:

npm install --save \

gatsby-plugin-canonical-urls \

gatsby-plugin-google-analytics \

gatsby-plugin-typescript \

gatsby-remark-autolink-headers \

gatsby-remark-copy-linked-files \

gatsby-remark-images \

gatsby-remark-responsive-iframe \

gatsby-remark-smartypants \

gatsby-transformer-json \

gatsby-transformer-remarkThis matches my setup for Gatsby. Because I tend to write about code I also want to support syntax-highlighting. Prism highlights code blocks in multiple languages:

npm install --save \

gatsby-remark-prismjs \

prism-themes \

prismjsWe’ll also want to add support for styled components:

npm install --save \

gatsby-plugin-styled-components \

styled-components \

babel-plugin-styled-components \

classnamesAnd TypeScript support:

npm install --save-dev typescriptFinally, because we’re using TypeScript, we’ll want to add type support for development:

npm install --save-dev \

@types/node \

@types/jest \

@types/prop-types \

@types/react \

@types/react-dom \

@types/react-helmet \

@types/classnames \

@types/styled-componentsOur website still doesn’t work, but this is a good opportunity to create another commit; check the status:

git statusYou should see:

On branch master

Untracked files:

(use "git add <file>..." to include in what will be committed)

package-lock.json

package.json

nothing added to commit but untracked files present (use "git add" to track)We’ve added files to our project but many of them are ignored. For example, the node_modules folder contains tons of files (as mentioned before), but it isn’t necessary to keep those in our version control (git) because they can easily be reinstalled on any machine. We want everyone working on our project to install the same dependencies. When installing, they were automatically added to the package.json file and the package-lock.json. The package-lock.json ensures that the dependencies of our packages are locked to specific versions. Because of this, we’ll add both of these files to git:

git add .And then commit:

git commit -m "Setting up our packages"Setting up Gatsby

At this point we have a solid foundation but not much to show for it. Let’s configure Gatsby so that we can see some output. Gatsby is made up of a collection of packages, many of which are optional based on your particular use case. Which packages you choose to use is configured in three files:

gatsby-config.js- general configuration and pluginsgatsby-node.js- build time and development generation and resolversgatsby-browser.js- client side code bundled to run in a user’s browsergatsby-ssr.js- code that should run when server-side rendering (we won’t use this)

Configuration - gatsby-config.js

The configuration is broken down into two main sections: siteMetadata and a list of plugins, some of which have custom options. Replace your gatsby-config.js file with the following:

/* eslint-disable @typescript-eslint/camelcase */

'use strict'

module.exports = {

siteMetadata: {

title: 'Example',

description: 'This is an example site I made.',

siteUrl: 'https://example.com',

author: {

name: 'Jeff Rafter',

url: 'https://twitter.com/jeffrafter',

email: 'jeffrafter@gmail.com',

},

social: {

twitter: 'https://twitter.com/jeffrafter',

github: 'https://github.com/jeffrafter',

},

},

plugins: [

{

resolve: `gatsby-source-filesystem`,

options: {

path: `${__dirname}/content/posts`,

name: `posts`,

},

},

{

resolve: `gatsby-source-filesystem`,

options: {

path: `${__dirname}/content/assets`,

name: `assets`,

},

},

{

resolve: `gatsby-transformer-remark`,

options: {

plugins: [

{

resolve: `gatsby-remark-images`,

options: {

maxWidth: 1280,

},

},

{

resolve: `gatsby-remark-responsive-iframe`,

options: {

wrapperStyle: `margin-bottom: 1.0725rem`,

},

},

`gatsby-remark-autolink-headers`,

`gatsby-remark-prismjs`,

`gatsby-remark-copy-linked-files`,

`gatsby-remark-smartypants`,

],

},

},

{

resolve: `gatsby-plugin-canonical-urls`,

options: {

siteUrl: `https://jeffrafter.com`,

},

},

{

resolve: `gatsby-plugin-manifest`,

options: {

name: `Jeff Rafter`,

short_name: `jeffrafter.com`,

start_url: `/`,

background_color: `#ffffff`,

theme_color: `#663399`,

display: `minimal-ui`,

icon: `src/images/gatsby-icon.png`, // This path is relative to the root of the site.,

},

},

{

resolve: `gatsby-plugin-google-analytics`,

options: {

// trackingId: `ADD YOUR TRACKING ID HERE`,

},

},

`gatsby-plugin-react-helmet`,

`gatsby-plugin-sharp`,

`gatsby-plugin-styled-components`,

`gatsby-plugin-typescript`,

`gatsby-transformer-sharp`,

],

}Let’s break down each part.

siteMetadata

The siteMetadata section is entirely custom. You can put whatever you want in here and later use it in your pages (using GraphQL, which we’ll cover later). The fields that I’ve specified are commonly used by different Gatsby sites and are often supported in different plugins and themes.

siteMetadata: {

title: 'Example',

description: 'This is an example site I made.',

siteUrl: 'https://example.com',

author: {

name: 'Jeff Rafter',

url: 'https://twitter.com/jeffrafter',

email: 'jeffrafter@gmail.com',

},

social: {

twitter: 'https://twitter.com/jeffrafter',

github: 'https://github.com/jeffrafter',

},

},plugins

There are a list of plugins. Like the siteMetadata section you have a lot of choices.

gatsby-source-filesystem

The first two plugins are actually all the same: gatsby-source-filesystem. This allows us to

use files in our folder to generate our website. In this case we’ve split the site content into

two different folders:

content/postscontent/assets

This isn’t a requirement, it just helps us with organization later:

{

resolve: `gatsby-source-filesystem`,

options: {

path: `${__dirname}/content/posts`,

name: `posts`,

},

},

{

resolve: `gatsby-source-filesystem`,

options: {

path: `${__dirname}/content/assets`,

name: `assets`,

},

},You’ll see these sources used when we dig into the gatsby-node.js configuration.

Once you’ve made this change and saved your configuration your Gatsby site will break. That’s because we haven’t created those folders. In your terminal run the following:

mkdir -p content/posts

mkdir -p content/assetsgatsby-transformer-remark

Gatsby has a class of plugins called “transformers”. These plugins take the content (from the folders specified above) and transform them to be viewable as HTML (and other formats). Remark is a transformer based on Remarkable which converts Markdown content to HTML. Markdown is a text format that is intended to be quicker and easier to type – while giving you a consistent output.Want to know more about Markdown? It was created by John Gruber and Aaron Swartz and initially released on Daring Fireball. For more information on how it works, check out the guide.

The output can be more complex, and because of that there are a set of plugins that extend Remarkable listed as well:

{

resolve: `gatsby-transformer-remark`,

options: {

plugins: [

{

resolve: `gatsby-remark-images`,

options: {

maxWidth: 1280,

},

},

{

resolve: `gatsby-remark-responsive-iframe`,

options: {

wrapperStyle: `margin-bottom: 1.0725rem`,

},

},

`gatsby-remark-autolink-headers`,

`gatsby-remark-prismjs`,

`gatsby-remark-copy-linked-files`,

`gatsby-remark-smartypants`,

],

},

},The extensions:

gatsby-remark-images- autosizes the images so they fit better with the rest of the contentgatsby-remark-prismjs- syntax highlighting for code blocksgatsby-remark-responsive-iframe- allows iframes to resize correctlygatsby-remark-autolink-headers- adds a link target (and<a>) to each header in your postsgatsby-remark-copy-linked-files- copies externally linked files to your project on buildgatsby-remark-smartypants- converts quotes and apostropes to smart-quotes and smart-apostrophes

gatsby-plugin-sharp and gatsby-transformer-sharp

The sharp image plugin and transformer enhance and size your images. These work together with

gatsby-remark-imagesbut can also be used on other images throughout your site.

gatsby-plugin-manifest

Do you have a fancy favicon? Do you want it to work in every browser and mobile device and also work as a home-screen icon and Desktop cover photo? Generating all of those and creating a manifest to refer to them is cumbersome… unless you use gatsby-plugin-manifest:

{

resolve: `gatsby-plugin-manifest`,

options: {

name: `Jeff Rafter`,

short_name: `jeffrafter.com`,

start_url: `/`,

background_color: `#ffffff`,

theme_color: `#663399`,

display: `minimal-ui`,

icon: `src/images/gatsby-icon.png`, // This path is relative to the root of the site.,

},

},Right now, our icon image is the Gatsby logo. Feel free to customize the icon.

gatsby-plugin-canonical-urls

When you deploy your website you may have a custom domain name like jeffrafter.com. However you might have additional ways to get to your site such as www.jeffrafter.com or jeffrafter.github.io. When Google’s search engine sees the same content at three different sites it thinks something is fishy. Setting a “canonical URL” tells Google (and others), “Hey, if you find this content via different URLs, just ignore that and use the canonical URL.”

{

resolve: `gatsby-plugin-canonical-urls`,

options: {

siteUrl: `https://jeffrafter.com`,

},

},gatsby-plugin-google-analytics

If you want to use Google Analytics you can add it via the plugin and all of the default scripts will be injected automatically:

{

resolve: `gatsby-plugin-google-analytics`,

options: {

// trackingId: `ADD YOUR TRACKING ID HERE`,

},

},gatsby-plugin-react-helmet

Though we’ve included some plugins that inject content into the <head> of each webpage, you may want to include custom content, such as OpenGraph tags or Twitter cards. For this, you’ll need react-helmet. React generally focuses on the <body> of webpages, but react-helmet focuses on the <head>.

gatsby-plugin-styled-components

Gatbsy has good support for styled components (or CSS-in-js). Many Gatsby users use Emotion. I tend to prefer the patterns in https://www.styled-components.com/ which this plugin enables.

gatsby-plugin-typescript

We’ll be developing in TypeScript. This plugin adds support (including typings) to help while developing.

Build time and development server - gatsby-node.js

When developing your website or when building, Gatsby (running on Node) relies on the setup in gatsby-node.jsNotice that this file has a .js extension? When I said we would be building our site in TypeScript I meant most of the site. Writing the config files in JavaScript is a little easier and once you've written them they tend to not change.. This is where all of the pages for the website are transformed and generated. As with other parts of Gatsby there are lots of options here. For our setup, we need to export two functions:

createPages = ({graphql, actions}).onCreateNode = ({node, actions, getNode})

Open gatsby-node.js and replace the contents:

const path = require(`path`)

const {createFilePath} = require(`gatsby-source-filesystem`)

exports.createPages = ({graphql, actions}) => {

return graphql(

`

{

allMarkdownRemark(sort: {fields: [frontmatter___date], order: DESC}, limit: 1000) {

edges {

node {

fields {

slug

}

frontmatter {

tags

title

}

}

}

}

}

`,

).then(result => {

if (result.errors) {

throw result.errors

}

// Get the templates

const postTemplate = path.resolve(`./src/templates/post.tsx`)

const tagTemplate = path.resolve('./src/templates/tag.tsx')

// Create post pages

const posts = result.data.allMarkdownRemark.edges

posts.forEach((post, index) => {

const previous = index === posts.length - 1 ? null : posts[index + 1].node

const next = index === 0 ? null : posts[index - 1].node

actions.createPage({

path: post.node.fields.slug,

component: postTemplate,

context: {

slug: post.node.fields.slug,

previous,

next,

},

})

})

// Iterate through each post, putting all found tags into `tags`

let tags = []

posts.forEach(post => {

if (post.node.frontmatter.tags) {

tags = tags.concat(post.node.frontmatter.tags)

}

})

const uniqTags = [...new Set(tags)]

// Create tag pages

uniqTags.forEach(tag => {

if (!tag) return

actions.createPage({

path: `/tags/${tag}/`,

component: tagTemplate,

context: {

tag,

},

})

})

})

}

exports.onCreateNode = ({node, actions, getNode}) => {

if (node.internal.type === `MarkdownRemark`) {

const value = createFilePath({node, getNode})

actions.createNodeField({

name: `slug`,

node,

value,

})

}

}Let’s break it down piece by piece. We’ll start off by requiring a couple of packages we’ll need:

const path = require(`path`)

const {createFilePath} = require(`gatsby-source-filesystem`)Next we’ll write the createPages function. The function starts with a GraphQL query. GraphQL is an API that accesses a datastore— in this case Gatsby itself. The plugins that we’ve installed into Gatsby provide content; specifically the gatsby-filsesystem-source grabs all of the files in the specified locations and transforms them using gatsby-transformer-remark.This provides a resource containing the rendered markdown.

return graphql(

`

{

allMarkdownRemark(sort: {fields: [frontmatter___date], order: DESC}, limit: 1000) {

edges {

node {

fields {

slug

}

frontmatter {

tags

title

}

}

}

}

}

`,

)We execute the query (asynchronously), selecting the specific fields we want. Each markdown file will have frontmatter: a formatted set of fields before the Markdown content starts. For example:

---

title: Basic Gatsby Site with TypeScript

date: '2019-05-25T00:01:00'

published: true

slug: basic-gatsby-with-typescript

layout: post

tags: ['javascript', 'typescript', 'node', 'gatsby']

category: Web

---Each one of these fields is available as items in the frontmatter connection in GraphQL. However, if you try to access an item via GraphQL and it is not listed in the frontmatter of every page you’ll get an error. For this reason we only grab the tags and the title and require that these are set in the frontmatter of each post.

Once the GraphQL query completes we handle the result. If there is an error we immediately throw it. This only happens at development or build time so throwing the error should give us immediately useful feedback:

if (result.errors) {

throw result.errors

}In the next part of the function we setup our templates. We have two kinds of pages:

- Post pages

- Tag pages

// Get the templates

const postTemplate = path.resolve(`./src/templates/post.tsx`)

const tagTemplate = path.resolve('./src/templates/tag.tsx')We’ll construct these templates a little later.

Next we’ll use the data we fetched (now in the GraphQL result) and generate each page using the

actions.createPage method that was passed to us:

// Create post pages

const posts = result.data.allMarkdownRemark.edges

posts.forEach((post, index) => {

const previous = index === posts.length - 1 ? null : posts[index + 1].node

const next = index === 0 ? null : posts[index - 1].node

actions.createPage({

path: post.node.fields.slug,

component: postTemplate,

context: {

slug: post.node.fields.slug,

previous,

next,

},

})

})Notice that we are checking for a previous and next page and passing them into the context field when we create the page. Each of the context fields will be converted to props we can use in our React templates. The previous and next allow us to build a carousel in the footer of our pages.

At a minimum our website should be able to display the posts we write. For my website I wanted to be able to add tags to posts to easily group them together. In the frontmatter I can supply a list of tags:

tags: ['javascript', 'typescript', 'node', 'gatsby']In our generator we’ll loop through all of the posts and grab all of the tags. Once we have

them all we’ll make them unique (using the Set trick) so that there are no duplicates. For

each tag we’ll create a new page using our tag template:

// Iterate through each post, putting all found tags into `tags`

let tags = []

posts.forEach(post => {

if (post.node.frontmatter.tags) {

tags = tags.concat(post.node.frontmatter.tags)

}

})

const uniqTags = [...new Set(tags)]

// Create tag pages

uniqTags.forEach(tag => {

if (!tag) return

actions.createPage({

path: `/tags/${tag}/`,

component: tagTemplate,

context: {

tag,

},

})

})With this we can create all of the pages. There is one small problem: in our GraphQL query we

selected the slug field:

fields {

slug

}This field doesn’t exist by default – we’ll need to create it. We can do this by adding an onCreateNode function to our gatsby-node.js file:

exports.onCreateNode = ({node, actions, getNode}) => {

if (node.internal.type === `MarkdownRemark`) {

const value = createFilePath({node, getNode})

actions.createNodeField({

name: `slug`,

node,

value,

})

}

}Whenever a node is created this function will be called. If it is a MarkdownRemark node we’ll create a new field called slug that we generate based on the filename.

Client side - gatsby-browser.js

In general, you want to keep the client side JavaScript and stylesheets as minimal as possible. This helps your pages load fast and keeps users (and Lighthouse checks) happy. Some of the plugins we’ve chosen will generate client-side JavaScript automatically. In fact, for our setup we only need to add one requirement. Replace the contents of gatsby-browser.js with:

require('prismjs/themes/prism.css')This will inject the CSS for our syntax highlighting into the downloadable payload.

Save your progress

With our configuration complete we should create another commit:

git statusYou should see:

On branch master

Untracked files:

(use "git add <file>..." to include in what will be committed)

gatsby-browser.js

gatsby-config.js

gatsby-node.js

nothing added to commit but untracked files present (use "git add" to track)Add those files:

git add .And commit them:

git commit -m "Configuring Gatsby"Building the site structure: layout, pages, templates, styles and components

Now that we have the configuration of the site we’ll need to setup the structure. By default, the Gatsby quick start created a usable site. This is super-helpful, but all of it is written in plain JavaScript and we want to use TypeScript so we’ll be replacing the files that were generated. While we’re at it, we’ll add some additional features.

Let’s start by completely removing and recreating the components and pages folders inside of the src folder:

rm -rf src/components

rm -rf src/pagesThe new file structure still includes things like the header and footer on each page and how the pages look. We’ll create the about page the index and more.

|- src/

| |- images/

| | |- gatsby-astronaut.png

| | |- gatsby-icon.png

| |- components/

| | |- layout.tsx

| | |- head.tsx

| | |- bio.tsx

| |- pages/

| | |- 404.tsx

| | |- index.tsx

| | |- about.tsx

| | |- tags.tsx

| |- templates/

| | |- post.tsx

| | |- tag.tsx

| |- styles/

| | |- theme.tsNotice that most of these files are in the src folder - it is common to put the files that control how your site functions in the src folder. Content files, like blog posts, will go in a content folder.

Let’s create the new folders:

mkdir -p src/styles

mkdir -p src/components

mkdir -p src/pages

mkdir -p src/templatesStyles

For some, the design and presentation of a website is the most important aspect. There are a lot of options when theming a Gatsby site (a giant inlined CSS stylesheet isn’t necessarily ideal). For example, we could split our CSS into modules, rely only on locally styled components, or fully support Gatsby themes.When Gatsby was introduced it had very little support for custom themes. In fact, changing

the theme of the site was done primarily by creating a site from a new starter template. There are lots of starters available and changing themes wasn't very common so everything worked out. As Gatsby's popularity increased, the need for theming increased and themes were added. You can check those out on the Gatsby Site. For now we will start with something very basic: a simple CSS reset and an inline stylesheet. Create the file src/styles/theme.ts:

import styled, {css, createGlobalStyle} from 'styled-components'

export {css, styled}

export const theme = {

colors: {

black: '#000000',

background: '#fffff8',

contrast: '#111',

contrastLightest: '#dad9d9',

accent: 'red',

white: '#ffffff',

},

}

const reset = () => `

html {

box-sizing: border-box;

margin: 0;

padding: 0;

}

*, *::before, *::after {

box-sizing: inherit;

}

body {

margin: 0 !important;

padding: 0;

}

::selection {

background-color: ${theme.colors.contrastLightest};

color: rgba(0, 0, 0, 0.70);

}

a.anchor, a.anchor:hover, a.anchor:link {

background: none !important;

}

figure {

a.gatsby-resp-image-link {

background: none;

}

span.gatsby-resp-image-wrapper {

max-width: 100% !important;

}

}

`

// These style are based on https://edwardtufte.github.io/tufte-css/

const styles = () => `

html {

font-size: 15px;

}

body {

width: 87.5%;

margin-left: auto;

margin-right: auto;

padding-left: 12.5%;

font-family: Palatino, 'Palatino Linotype', 'Palatino LT STD', 'Book Antiqua', Georgia, serif;

background-color: white;

color: #111;

max-width: 1400px;

}

h1 {

font-weight: 400;

margin-top: 4rem;

margin-bottom: 1.5rem;

font-size: 3.2rem;

line-height: 1;

}

h2 {

font-style: italic;

font-weight: 400;

margin-top: 2.1rem;

margin-bottom: 1.4rem;

font-size: 2.2rem;

line-height: 1;

}

h3 {

font-style: italic;

font-weight: 400;

font-size: 1.7rem;

margin-top: 2rem;

margin-bottom: 1.4rem;

line-height: 1;

}

hr {

display: block;

height: 1px;

width: 55%;

border: 0;

border-top: 1px solid #ccc;

margin: 1em 0;

padding: 0;

}

article {

position: relative;

padding: 5rem 0rem;

}

section {

padding-top: 1rem;

padding-bottom: 1rem;

}

p,

ol,

ul {

font-size: 1.4rem;

line-height: 2rem;

}

p {

margin-top: 1.4rem;

margin-bottom: 1.4rem;

padding-right: 0;

vertical-align: baseline;

}

blockquote {

font-size: 1.4rem;

}

blockquote p {

width: 55%;

margin-right: 40px;

}

blockquote footer {

width: 55%;

font-size: 1.1rem;

text-align: right;

}

section > p,

section > footer,

section > table {

width: 55%;

}

section > ol,

section > ul {

width: 50%;

-webkit-padding-start: 5%;

}

li:not(:first-child) {

margin-top: 0.25rem;

}

figure {

padding: 0;

border: 0;

font-size: 100%;

font: inherit;

vertical-align: baseline;

max-width: 55%;

-webkit-margin-start: 0;

-webkit-margin-end: 0;

margin: 0 0 3em 0;

}

figcaption {

float: right;

clear: right;

margin-top: 0;

margin-bottom: 0;

font-size: 1.1rem;

line-height: 1.6;

vertical-align: baseline;

position: relative;

max-width: 40%;

}

figure.fullwidth figcaption {

margin-right: 24%;

}

a:link,

a:visited {

color: inherit;

}

img {

max-width: 100%;

}

div.fullwidth,

table.fullwidth {

width: 100%;

}

div.table-wrapper {

overflow-x: auto;

font-family: 'Trebuchet MS', 'Gill Sans', 'Gill Sans MT', sans-serif;

}

code {

font-family: Consolas, 'Liberation Mono', Menlo, Courier, monospace;

font-size: 1rem;

line-height: 1.42;

}

h1 > code,

h2 > code,

h3 > code {

font-size: 0.8em;

}

pre.code {

font-size: 0.9rem;

width: 52.5%;

margin-left: 2.5%;

overflow-x: auto;

}

pre.code.fullwidth {

width: 90%;

}

.fullwidth {

max-width: 100%;

clear: both;

}

.iframe-wrapper {

position: relative;

padding-bottom: 56.25%; /* 16:9 */

padding-top: 25px;

height: 0;

}

.iframe-wrapper iframe {

position: absolute;

top: 0;

left: 0;

width: 100%;

height: 100%;

}

@media (max-width: 760px) {

body {

width: 84%;

padding-left: 8%;

padding-right: 8%;

}

hr,

section > p,

section > footer,

section > table {

width: 100%;

}

pre.code {

width: 97%;

}

section > ol {

width: 90%;

}

section > ul {

width: 90%;

}

figure {

max-width: 90%;

}

figcaption,

figure.fullwidth figcaption {

margin-right: 0%;

max-width: none;

}

blockquote {

margin-left: 1.5em;

margin-right: 0em;

}

blockquote p,

blockquote footer {

width: 100%;

}

label.margin-toggle:not(.sidenote-number) {

display: inline;

}

label {

cursor: pointer;

}

div.table-wrapper,

table {

width: 85%;

}

img {

width: 100%;

}

}

`

export const GlobalStyle = createGlobalStyle`

${reset()}

${styles()}

`The important pieces here are createGlobalStyle and the generic reset. The styles that are in the styles function are based on Edward Tufte’s styles. This provides a very minimalist theme to build on.

Layout

Now that we have our basic styles we can move on to the layout. A website’s layout includes the header of the page, the site navigation, and the site’s footer that appears on every page. It is the thing that makes each page feel consistent. Create src/components/layout.tsx:

import React from 'react'

import {Link} from 'gatsby'

import {GlobalStyle, styled} from '../styles/theme'

const StyledNav = styled.nav`

ul {

list-style-type: none;

margin: 0;

padding: 0;

}

li {

display: inline-block;

margin: 16px;

a {

background: none;

}

}

`

const StyledFooter = styled.footer`

padding-bottom: 36px;

`

interface Props {

readonly title?: string

readonly children: React.ReactNode

}

const Layout: React.FC<Props> = ({children}) => (

<>

<GlobalStyle />

<StyledNav className="navigation">

<ul>

<li>

<Link to={`/`}>&</Link>

</li>

<li>

<Link to={`/tags`}>Tags</Link>

</li>

<li>

<Link to={`/about`}>About</Link>

</li>

</ul>

</StyledNav>

<main className="content" role="main">

{children}

</main>

<StyledFooter className="footer">

© {new Date().getFullYear()},{` `}

<a href="https://jeffrafter.com">jeffrafter.com</a>. Built with

{` `}

<a href="https://www.gatsbyjs.org">Gatsby</a>

</StyledFooter>

</>

)

export default LayoutFirst, we create a couple of custom styled components:

StyledNavStyledFooter

Styled components allow you to inject custom CSS at the component level and in this case are only used in this file. We can name them anything we want but it is common to prefix the name with Styled.

We then declare the Props interface. Declaring interfaces and types is what gives TypeScript its power.

interface Props {

readonly title?: string

readonly children: React.ReactNode

}Here we are saying that the component can accept an optional title property. We’ve also declared that our component will accept (and use) children elements. We get that for free (it is inherited) from the generic React.Component but we still need to declare it.

The Layout itself, is a simple React Functional Component (FC; it is a component that is just a function). We use the styled components we created to build a small site-navigation with links to our main pages, we have a main content area and a footer. The only other component is the global style declaration:

<GlobalStyle />We inject this inside our layout (not in the <head>) so that changes to the style will trigger a re-render when using hot-module-reloading.

Head

Like the Layout component, the Head component will be used on every page. We’ll use it to setup keywords, <meta> tags (like OpenGraph tags and Twitter cards) and more. Create the file src/components/head.tsx:

import React from 'react'

import Helmet from 'react-helmet'

import {StaticQuery, graphql} from 'gatsby'

type StaticQueryData = {

site: {

siteMetadata: {

title: string

description: string

author: {

name: string

}

}

}

}

interface Props {

readonly title: string

readonly description?: string

readonly lang?: string

readonly keywords?: string[]

}

const Head: React.FC<Props> = ({title, description, lang, keywords}) => (

<StaticQuery

query={graphql`

query {

site {

siteMetadata {

title

description

author {

name

}

}

}

}

`}

render={(data: StaticQueryData): React.ReactElement | null => {

const metaDescription = description || data.site.siteMetadata.description

lang = lang || 'en'

keywords = keywords || []

return (

<Helmet

htmlAttributes={{

lang,

}}

title={title}

titleTemplate={`%s | ${data.site.siteMetadata.title}`}

meta={[

{

name: `description`,

content: metaDescription,

},

{

property: `og:title`,

content: title,

},

{

property: `og:description`,

content: metaDescription,

},

{

property: `og:type`,

content: `website`,

},

{

name: `twitter:card`,

content: `summary`,

},

{

name: `twitter:creator`,

content: data.site.siteMetadata.author.name,

},

{

name: `twitter:title`,

content: title,

},

{

name: `twitter:description`,

content: metaDescription,

},

].concat(

keywords.length > 0

? {

name: `keywords`,

content: keywords.join(`, `),

}

: [],

)}

/>

)

}}

/>

)

export default HeadThe first thing we do is declare a StaticQueryData type. When the <Head> component is built we execute a <StaticQuery>. This is a GraphQL query that will execute and fetch results from Gatsby similarly to the gatsby-node.js query we saw earlier:

query={graphql`

query {

site {

siteMetadata {

title

description

author {

name

}

}

}

}

`}In this query we are accessing siteMetadata which we setup earlier in gatsby-config.js. Because we are using TypeScript we want to declare a type for the expected result and each of its fields:

type StaticQueryData = {

site: {

siteMetadata: {

title: string

description: string

author: {

name: string

}

}

}

}The type and the query are very similar. If you add a field to one of them you have to add it to the other. The query prop of StaticQuery is executed and the results are passed to the render function declared in the render prop.

We’ll use the default configuration for most props but allow some overrides to be passed in. For example each page may choose to have a different title so we allow that to be passed in. The header is rendered using a <Helmet> element from react-helmet.

Bio

Creating a Bio component isn’t required. I’ve created one mostly as a placeholder in case I want to add more components throughout the site. Create src/components/bio.tsx:

import React from 'react'

import {StaticQuery, graphql} from 'gatsby'

type StaticQueryData = {

site: {

siteMetadata: {

description: string

social: {

twitter: string

}

}

}

}

const Bio: React.FC = () => (

<StaticQuery

query={graphql`

query {

site {

siteMetadata {

description

social {

twitter

}

}

}

}

`}

render={(data: StaticQueryData): React.ReactElement | null => {

const {description, social} = data.site.siteMetadata

return (

<div>

<h1>{description}</h1>

<p>

By Jeff Rafter

<br />

<a href={social.twitter}>Twitter</a>

</p>

</div>

)

}}

/>

)

export default BioThis component is very similar to our Head component. It uses a <StaticQuery> declaration to execute a GraphQL query to fetch some values from our siteMetadata config. Then it renders the results. We could expand this component if we wanted to, possibly allowing for an author prop to be passed in the event that we had multiple authors.

Pages

With the basic structure like Layout and Head in place we can start building out individual pages. When the user attempts to navigate to a particular page Gatsby will first look for a corresponding page created via createPages in gatsby-node.js. If it doesn’t find the page there it will next look for a page in src/pagesAccording to the Gatsby structure docs: "Components under src/pages become pages automatically with paths based on their file name." You can find more about it in the pages documentation..

For example, if a user goes to /about, Gatsby will try to find src/pages/about.tsx. For the root page of the site (also known as the index) we can create a file called src/pages/index.tsx. Each page in the src/pages folder should export a default React component. Additionally, it can export a pageQuery constant. The pageQuery constant is a GraphQL query that will be executed prior to rendering the component. The results from the query will be passed into the component as a prop called data.

index Page

The index is the home page of our website. Create the file src/pages/index.tsx:

import React from 'react'

import {Link, graphql} from 'gatsby'

import Layout from '../components/layout'

import Head from '../components/head'

import Bio from '../components/bio'

interface Props {

readonly data: PageQueryData

}

const Index: React.FC<Props> = ({data}) => {

const siteTitle = data.site.siteMetadata.title

const posts = data.allMarkdownRemark.edges

return (

<Layout title={siteTitle}>

<Head title="All posts" keywords={[`blog`, `gatsby`, `javascript`, `react`]} />

<Bio />

<article>

<div className={`page-content`}>

{posts.map(({node}) => {

const title = node.frontmatter.title || node.fields.slug

return (

<div key={node.fields.slug}>

<h3>

<Link to={node.fields.slug}>{title}</Link>

</h3>

<small>{node.frontmatter.date}</small>

<p dangerouslySetInnerHTML={{__html: node.excerpt}} />

</div>

)

})}

</div>

</article>

</Layout>

)

}

interface PageQueryData {

site: {

siteMetadata: {

title: string

}

}

allMarkdownRemark: {

edges: {

node: {

excerpt: string

fields: {

slug: string

}

frontmatter: {

date: string

title: string

}

}

}[]

}

}

export const pageQuery = graphql`

query {

site {

siteMetadata {

title

}

}

allMarkdownRemark(

filter: {frontmatter: {published: {ne: false}}}

sort: {fields: [frontmatter___date], order: DESC}

) {

edges {

node {

excerpt

fields {

slug

}

frontmatter {

date(formatString: "MMMM DD, YYYY")

title

}

}

}

}

}

`

export default IndexLet’s break this down. We start of by importing the components we created earlier:

import Layout from '../components/layout'

import Head from '../components/head'

import Bio from '../components/bio'Then we declare an interface for the Props we expect to receive when this component is rendered. As we saw earlier, pages in Gatsby are passed the result of a GraphQL query.

interface Props {

readonly data: PageQueryData

}The type of data is PageQueryData. We haven’t declared that type yet; it’s declared lower in index.tsx.

The Index component itself is fairly straightforward. We render all of the content in the page inside of a <Layout> component (imported above) so that the page looks consistent with the rest of the site. We’ve included the <Head> and <Bio> for the same reason. The rest of the content is a list of articles constructed by looping through the data:

const Index: React.FC<Props> = ({data}) => {

const siteTitle = data.site.siteMetadata.title

const posts = data.allMarkdownRemark.edges

return (

<Layout title={siteTitle}>

<Head title="All posts" keywords={[`blog`, `gatsby`, `javascript`, `react`]} />

<Bio />

<article>

<div className={`page-content`}>

{posts.map(({node}) => {

const title = node.frontmatter.title || node.fields.slug

return (

<div key={node.fields.slug}>

<h3>

<Link to={node.fields.slug}>{title}</Link>

</h3>

<small>{node.frontmatter.date}</small>

<p dangerouslySetInnerHTML={{__html: node.excerpt}} />

</div>

)

})}

</div>

</article>

</Layout>

)

}Notice that we link to each page using the <Link> object. Gatsby is really great at rendering content on the client side and the <Link> component helps handle that routing where possible.

Lastly, we construct the query and the corresponding interface:

interface PageQueryData {

site: {

siteMetadata: {

title: string

}

}

allMarkdownRemark: {

edges: {

node: {

excerpt: string

fields: {

slug: string

}

frontmatter: {

date: string

title: string

}

}

}[]

}

}

export const pageQuery = graphql`

query {

site {

siteMetadata {

title

}

}

allMarkdownRemark(

filter: {frontmatter: {published: {ne: false}}}

sort: {fields: [frontmatter___date], order: DESC}

) {

edges {

node {

excerpt

fields {

slug

}

frontmatter {

date(formatString: "MMMM DD, YYYY")

title

}

}

}

}

}

`Again, we could have selected any of the fields we wanted (we aren’t required to select them all).

about Page

The /about page follows the same pattern of the Index. Create a file

called src/pages/about.tsx:

import React from 'react'

import {graphql} from 'gatsby'

import Layout from '../components/layout'

import Head from '../components/head'

interface Props {

readonly data: PageQueryData

}

const About: React.FC<Props> = ({data}) => {

const siteTitle = data.site.siteMetadata.title

return (

<Layout title={siteTitle}>

<Head title="All tags" keywords={[`blog`, `gatsby`, `javascript`, `react`]} />

<article>About Jeff Rafter...</article>

</Layout>

)

}

interface PageQueryData {

site: {

siteMetadata: {

title: string

}

}

}

export const pageQuery = graphql`

query {

site {

siteMetadata {

title

}

}

}

`

export default AboutWe haven’t added any real content to this page; it is here more as a placeholder. If you want to add pages (such as a terms of service or privacy page), this file can serve as a basic example.

404 Page

The 404 page of website is what the user should see when they attempt to go to a page that

doesn’t exist. This page is special because it isn’t rendered based on the name. Create a

file called src/pages/404.tsx:

import React from 'react'

import {graphql} from 'gatsby'

import Layout from '../components/layout'

import Head from '../components/head'

interface Props {

readonly data: PageQueryData

}

export default class NotFoundPage extends React.Component<Props> {

render() {

const {data} = this.props

const siteTitle = data.site.siteMetadata.title

return (

<Layout title={siteTitle}>

<Head title="404: Not Found" />

<h1>Not Found</h1>

<p>You just hit a route that doesn't exist... the sadness.</p>

</Layout>

)

}

}

interface PageQueryData {

site: {

siteMetadata: {

title: string

}

}

}

export const pageQuery = graphql`

query {

site {

siteMetadata {

title

}

}

}

`tags Page

When we generated all of the pages in gatsby-node.js we created a page for each tag used in the frontmatter of our posts. Let’s add a page that lists all of the tags available on our site to make it easy to find those pages. Create a file called src/pages/tags.tsx:

import React from 'react'

import {Link, graphql} from 'gatsby'

import Layout from '../components/layout'

import Head from '../components/head'

interface Props {

readonly data: PageQueryData

}

const Tags: React.FC<Props> = ({data}) => {

const siteTitle = data.site.siteMetadata.title

const group = data.allMarkdownRemark && data.allMarkdownRemark.group

return (

<Layout title={siteTitle}>

<Head title="All tags" keywords={[`blog`, `gatsby`, `javascript`, `react`]} />

<article>

<h1>All tags</h1>

<div className={`page-content`}>

{group &&

group.map(

tag =>

tag && (

<div key={tag.fieldValue}>

<h3>

<Link to={`/tags/${tag.fieldValue}/`}>{tag.fieldValue}</Link>

</h3>

<small>

{tag.totalCount} post

{tag.totalCount === 1 ? '' : 's'}

</small>

</div>

),

)}

</div>

</article>

</Layout>

)

}

interface PageQueryData {

site: {

siteMetadata: {

title: string

}

}

allMarkdownRemark: {

group: {

fieldValue: string

totalCount: number

}[]

}

}

export const pageQuery = graphql`

query {

site {

siteMetadata {

title

}

}

allMarkdownRemark(filter: {frontmatter: {published: {ne: false}}}) {

group(field: frontmatter___tags) {

fieldValue

totalCount

}

}

}

`

export default TagsTemplates

We’ve created all of the pages and completed the configuration but we aren’t quite done. You’ll remember that when we generated the pages in gatsby-node.js we referred to the post and tag template files:

// Get the templates

const postTemplate = path.resolve(`./src/templates/post.tsx`)

const tagTemplate = path.resolve('./src/templates/tag.tsx')We haven’t created those templates yet. Let’s do that now:

post Template

The post template is used when rendering each post for our blog. Create a file called src/templates/post.tsx:

import React from 'react'

import {Link, graphql} from 'gatsby'

import {styled} from '../styles/theme'

import Layout from '../components/layout'

import Head from '../components/head'

interface Props {

readonly data: PageQueryData

readonly pageContext: {

// eslint-disable-next-line @typescript-eslint/no-explicit-any

previous?: any

// eslint-disable-next-line @typescript-eslint/no-explicit-any

next?: any

}

}

const StyledUl = styled('ul')`

list-style-type: none;

li::before {

content: '' !important;

padding-right: 0 !important;

}

`

const PostTemplate: React.FC<Props> = ({data, pageContext}) => {

const post = data.markdownRemark

const siteTitle = data.site.siteMetadata.title

const {previous, next} = pageContext

return (

<Layout title={siteTitle}>

<Head title={post.frontmatter.title} description={post.excerpt} />

<article>

<header>

<h1>{post.frontmatter.title}</h1>

<p>{post.frontmatter.date}</p>

</header>

<div className={`page-content`}>

<div dangerouslySetInnerHTML={{__html: post.html}} />

<StyledUl>

{previous && (

<li>

<Link to={previous.fields.slug} rel="prev">

← {previous.frontmatter.title}

</Link>

</li>

)}

{next && (

<li>

<Link to={next.fields.slug} rel="next">

{next.frontmatter.title} →

</Link>

</li>

)}

</StyledUl>

</div>

</article>

</Layout>

)

}

interface PageQueryData {

site: {

siteMetadata: {

title: string

}

}

markdownRemark: {

id?: string

excerpt?: string

html: string

frontmatter: {

title: string

date: string

}

}

}

export const pageQuery = graphql`

query BlogPostBySlug($slug: String!) {

site {

siteMetadata {

title

}

}

markdownRemark(fields: {slug: {eq: $slug}}) {

id

excerpt(pruneLength: 2500)

html

frontmatter {

title

date(formatString: "MMMM DD, YYYY")

}

}

}

`

export default PostTemplateThis page is very similar to the index and about pages. We export a default component and export a pageQuery object that Gatsby will execute before rendering. In addition to passing the data results from the GraphQL query, this template will also receive a pageContext object.

interface Props {

readonly data: PageQueryData

readonly pageContext: {

// eslint-disable-next-line @typescript-eslint/no-explicit-any

previous?: any

// eslint-disable-next-line @typescript-eslint/no-explicit-any

next?: any

}

}The pageContext object is actually constructed in the createPages function in gatsby-node.js. In our case we’ve passed a previous and next field (optional) so that we generate a carousel (previous and next links between posts) at the bottom of each post.You'll notice that the type of previous and next is any – in TypeScript this is considered bad practice and represents someone throwing their hands in the air saying "I have no idea what you are sending me." I'll leave these as an exercise for the reader.

Another interesting part of this template is the ominously named dangerouslySetInnerHTML.

<div dangerouslySetInnerHTML={{__html: post.html}} />We saw this earlier as well. What’s it doing here? When the gatsby-remark plugin converts our Markdown it generates HTML. Normally, if we inserted the HTML directly in our template it would all be escaped (for example & would become &). Not escaping HTML content is considered dangerous as it could introduce security vulnerabilities. In this case we know that the content we are injecting was already properly escaped (by the gatsby-remark plugin) and we know we can assign it directly. The prop dangerouslySetInnerHTML is named as such to prevent you using it on accident.

tag Template

The tag template is extremely similar to the post template. Create a file called src/templates/tag.tsx:

import React from 'react'

import {Link, graphql} from 'gatsby'

import Layout from '../components/layout'

import Head from '../components/head'

interface Props {

readonly data: PageQueryData

readonly pageContext: {

tag: string

}

}

const TagTemplate: React.FC<Props> = ({data, pageContext}) => {

const {tag} = pageContext

const siteTitle = data.site.siteMetadata.title

const posts = data.allMarkdownRemark.edges

return (

<Layout title={siteTitle}>

<Head

title={`Posts tagged "${tag}"`}

keywords={[`blog`, `gatsby`, `javascript`, `react`, tag]}

/>

<article>

<header>

<h1>Posts tagged {tag}</h1>

</header>

<div className={`page-content`}>

{posts.map(({node}) => {

const title = node.frontmatter.title || node.fields.slug

return (

<div key={node.fields.slug}>

<h3>

<Link to={node.fields.slug}>{title}</Link>

</h3>

<small>{node.frontmatter.date}</small>

<p dangerouslySetInnerHTML={{__html: node.excerpt}} />

</div>

)

})}

</div>

</article>

</Layout>

)

}

interface PageQueryData {

site: {

siteMetadata: {

title: string

}

}

allMarkdownRemark: {

totalCount: number

edges: {

node: {

excerpt: string

fields: {

slug: string

}

frontmatter: {

date: string

title: string

}

}

}[]

}

}

export const pageQuery = graphql`

query TagPage($tag: String) {

site {

siteMetadata {

title

}

}

allMarkdownRemark(limit: 1000, filter: {frontmatter: {tags: {in: [$tag]}}}) {

totalCount

edges {

node {

excerpt(pruneLength: 2500)

fields {

slug

}

frontmatter {

date

title

}

}

}

}

}

`

export default TagTemplateStatic content

Static assets like images, PDF documents, videos and embedded fonts will be used throughout a site. We’ve only referred to one static asset in our site so far: src/images/gatsby-icon.png. We linked to this in the manifest in gastby-config.js.

{

resolve: `gatsby-plugin-manifest`,

options: {

name: `Jeff Rafter`,

short_name: `jeffrafter.com`,

start_url: `/`,

background_color: `#ffffff`,

theme_color: `#663399`,

display: `minimal-ui`,

icon: `src/images/gatsby-icon.png`, // This path is relative to the root of the site.

},

},If you want to use images in your static folder elsewhere in the site you can place them in a static folder (a sibling folder of src) and import them directly:

import Logo from '../../static/logo.png'And then refer to returned URL:

<img src={Logo} width={24} />While this works well for many static files (including images), importing images using childImageSharp and utilizing Gatsby Image is generally the preferred way of including them.

In some cases you don’t need to import the files you put in the static folder but can refer to them directly and Gatsby will automatically expand the path. For more information, see the static asset documentation.

Save your progress

We’ve setup the entire structure of our Gatsby site. Really, we could have committed each of the files as we added them instead of creating a giant commit. Let’s commit again:

git statusYou should see:

On branch master

Untracked files:

(use "git add <file>..." to include in what will be committed)

src/

static/

nothing added to commit but untracked files present (use "git add" to track)It just shows the two folders we added to the root. Add those folders:

git add .Let’s check the status again:

git statusNow you should see:

On branch master

Changes to be committed:

(use "git reset HEAD <file>..." to unstage)

new file: src/components/bio.tsx

new file: src/components/head.tsx

new file: src/components/layout.tsx

new file: src/pages/404.tsx

new file: src/pages/about.tsx

new file: src/pages/index.tsx

new file: src/pages/tags.tsx

new file: src/styles/theme.ts

new file: src/templates/post.tsx

new file: src/templates/tag.tsx

new file: static/logo.pngWe’ve added everything recursively and all of the files we’ve created are staged for the next commit. Let’s commit them:

git commit -m "Adding styles, components, pages and templates"Writing posts

Writing content is the most important part of your blog and where you will spend most of your time. When writing a post you’ll create a markdown file in content/posts and store any images

in content/assets. If you haven’t already done so, make the folders:

mkdir -p content/posts

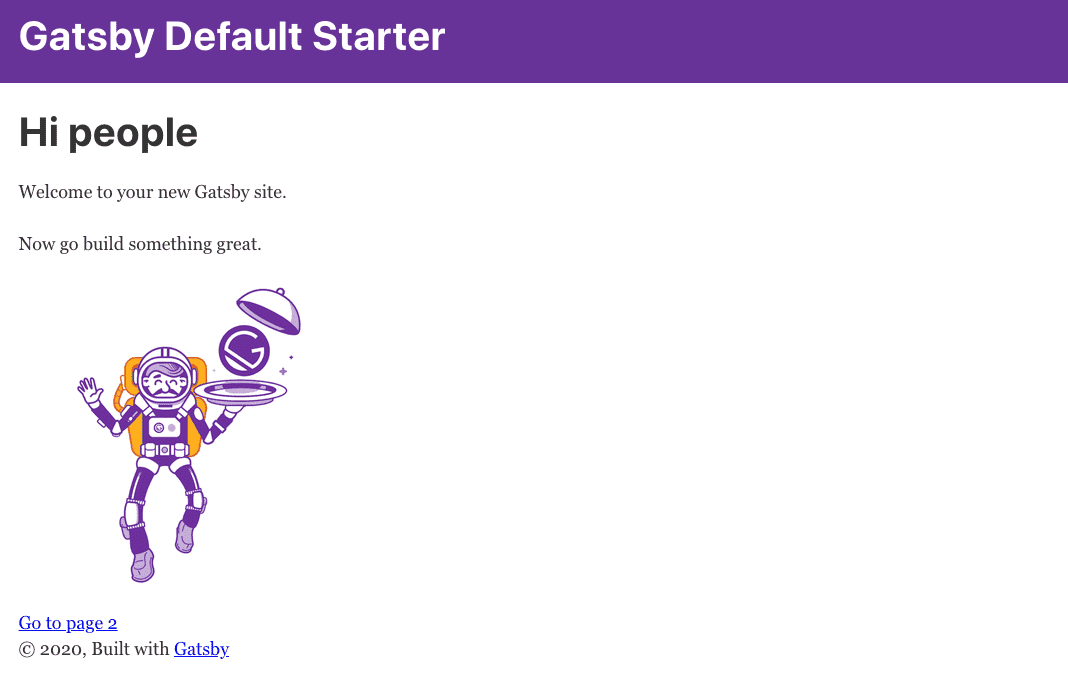

mkdir -p content/assetsNext, create a post by creating a file content/posts/hello-world.md:

---

title: Hello World

date: '2019-05-25'

published: true

layout: post

tags: ['markdown', 'hello', 'world']

category: example

---

Hello, this is an exciting post with three main points:

1. You can format your content using *markdown*

2. You can refer to images

3. You can include syntax highlighted code

```js

console.log(`Hello world, 1 + 1 = ${1 + 1}`);

```Copy this Furby image and save it as content/assets/furby.png:

Save your progress

That’s it, we have the first post and static content:

git statusYou should see:

On branch master

Untracked files:

(use "git add <file>..." to include in what will be committed)

content/

nothing added to commit but untracked files present (use "git add" to track)Add the content folder (and the files it contains):

git add .And commit them:

git commit -m "Initial post"Developing

Now that we have content, everything should work. To get started let’s run the development server:

npm run devThis will prepare the package and compile all of the pages, transforming the markdown and preparing and executing the GraphQL:

> @ dev /Users/example/Code/Examples/blog

> gatsby develop

success open and validate gatsby-configs - 0.035 s

success load plugins - 0.453 s

success onPreInit - 0.005 s

success initialize cache - 0.006 s

success copy gatsby files - 0.050 s

success onPreBootstrap - 0.010 s

success source and transform nodes - 0.055 s

success building schema - 0.250 s

success createPages - 0.033 s

success createPagesStatefully - 0.037 s

success onPreExtractQueries - 0.005 s

success update schema - 0.027 s

success extract queries from components - 0.126 s

success run static queries - 0.016 s — 2/2 161.46 queries/second

success run page queries - 0.061 s — 10/10 176.16 queries/second

success write out page data - 0.004 s

success write out redirect data - 0.002 s

success Build manifest and related icons - 0.113 s

success onPostBootstrap - 0.121 s

⠀

info bootstrap finished - 3.439 s

⠀

DONE Compiled successfully in 2230ms 12:15:58 PM

⠀

⠀

You can now view undefined in the browser.

⠀

http://localhost:8000/

⠀

View GraphiQL, an in-browser IDE, to explore your site's data and schema

⠀

http://localhost:8000/___graphql

⠀

Note that the development build is not optimized.

To create a production build, use npm run build

⠀

info ℹ 「wdm」:

info ℹ 「wdm」: Compiled successfully.At this point you should be able to open your website in your browser: http://localhost:8000/:

The server utilizes Hot-module-reloading (HMR) so that, as you make changes, your webpage will be immediately updated in the browser. This is true for themes, structure changs and content.

For some changes you do need to restart the server. Generally the changes that require a restart are related to configuration changes, for example in

gatsby-config.jsorgatsby-node.jsor if you add a new package to yourpackage.json.

Deploying

The power of Gatsby is that it can be served statically – you don’t need a server at all. There are lots of options for deploying. I’ve used the following:

- Netlify

- Now.sh

- AWS S3

- GitHub Pages

Since we have been keeping track of our changes in git, using GitHub Pages is a natural fit (and free forever). The Gatsby docs have an extensive set of tutorials on how to prepare and deploy your site: https://www.gatsbyjs.org/docs/deploying-and-hosting/

For me I used the gh-pages plugin and followed this tutorial: https://www.gatsbyjs.org/docs/how-gatsby-works-with-github-pages/.

All of the code (and commits) are available on GitHub: https://github.com/example-gatsby-typescript-blog/example-gatsby-typescript-blog.github.io

Comments

Thanks for reading ❤️ – comment by replying to the issue for this post. There’s no comments yet; you could be the first.

There’s more to read

Looking for more long-form posts? Here ya go...